Thermal conductivity

In physics, thermal conductivity,  , is the property of a material that indicates its ability to conduct heat. It appears primarily in Fourier's Law for heat conduction. Thermal conductivity is measured in watts per kelvin per metre (W·K−1·m−1). Multiplied by a temperature difference (in kelvins, K) and an area (in square metres, m2), and divided by a thickness (in metres, m) the thermal conductivity predicts the energy loss (in watts, W) through a piece of material.

, is the property of a material that indicates its ability to conduct heat. It appears primarily in Fourier's Law for heat conduction. Thermal conductivity is measured in watts per kelvin per metre (W·K−1·m−1). Multiplied by a temperature difference (in kelvins, K) and an area (in square metres, m2), and divided by a thickness (in metres, m) the thermal conductivity predicts the energy loss (in watts, W) through a piece of material.

The reciprocal of thermal conductivity is thermal resistivity.

Contents |

Measurement

Generally speaking, there are a number of possibilities to measure thermal conductivity, each of them suitable for a limited range of materials, depending on the thermal properties and the medium temperature. A distinction may be observed between steady-state and transient techniques.

In general, steady-state techniques perform a measurement when the temperature of the material measured does not change with time. This makes the signal analysis straightforward (steady state implies constant signals). The disadvantage is that a well-engineered experimental setup is usually needed. The Divided Bar (various types) is the most common device used for consolidated rock samples.

The transient techniques perform a measurement during the process of heating up. The advantage is that measurements can be made relatively quickly. Transient methods are usually carried out by needle probes.

Standards

- IEEE Standard 442-1981, "IEEE guide for soil thermal resistivity measurements", ISBN 0-7381-0794-8. See also soil thermal properties. [1] [1]

- IEEE Standard 98-2002, "Standard for the Preparation of Test Procedures for the Thermal Evaluation of Solid Electrical Insulating Materials", ISBN 0-7381-3277-2 [2] [2]

- ASTM Standard D5334-08, "Standard Test Method for Determination of Thermal Conductivity of Soil and Soft Rock by Thermal Needle Probe Procedure" [3]

- ASTM Standard D5470-06, "Standard Test Method for Thermal Transmission Properties of Thermally Conductive Electrical Insulation Materials" [3]

- ASTM Standard E1225-04, "Standard Test Method for Thermal Conductivity of Solids by Means of the Guarded-Comparative-Longitudinal Heat Flow Technique" [4]

- ASTM Standard D5930-01, "Standard Test Method for Thermal Conductivity of Plastics by Means of a Transient Line-Source Technique" [5]

- ASTM Standard D2717-95, "Standard Test Method for Thermal Conductivity of Liquids" [6]

- ISO 22007-2:2008 "Plastics -- Determination of thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity -- Part 2: Transient plane heat source (hot disc) method" [7]

- Note: What is called the k-value of construction materials (e.g. window glass) in the U.S., is called λ-value in Europe. What is called U-value (= the inverse of R-value) in the U.S., used to be called k-value in Europe, but is now also called U-value in Europe.

Definitions

The reciprocal of thermal conductivity is thermal resistivity, usually measured in kelvin-metres per watt (K·m·W−1). When dealing with a known amount of material, its thermal conductance and the reciprocal property, thermal resistance, can be described. Unfortunately, there are differing definitions for these terms.

Conductance

For general scientific use, thermal conductance is the quantity of heat that passes in unit time through a plate of particular area and thickness when its opposite faces differ in temperature by one kelvin. For a plate of thermal conductivity k, area A and thickness L this is kA/L, measured in W·K−1 (equivalent to: W/°C). Thermal conductivity and conductance are analogous to electrical conductivity (A·m−1·V−1) and electrical conductance (A·V−1).

There is also a measure known as heat transfer coefficient: the quantity of heat that passes in unit time through unit area of a plate of particular thickness when its opposite faces differ in temperature by one kelvin. The reciprocal is thermal insulance. In summary:

- thermal conductance = kA/L, measured in W·K−1

- thermal resistance = L/(kA), measured in K·W−1 (equivalent to: °C/W)

- heat transfer coefficient = k/L, measured in W·K−1·m−2

- thermal insulance = L/k, measured in K·m²·W−1.

The heat transfer coefficient is also known as thermal admittance

Resistance

When thermal resistances occur in series, they are additive. So when heat flows through two components each with a resistance of 1 °C/W, the total resistance is 2 °C/W.

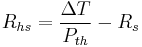

A common engineering design problem involves the selection of an appropriate sized heat sink for a given heat source. Working in units of thermal resistance greatly simplifies the design calculation. The following formula can be used to estimate the performance:

where:

- Rhs is the maximum thermal resistance of the heat sink to ambient, in °C/W

is the temperature difference (temperature drop), in °C

is the temperature difference (temperature drop), in °C- Pth is the thermal power (heat flow), in watts

- Rs is the thermal resistance of the heat source, in °C/W

For example, if a component produces 100 W of heat, and has a thermal resistance of 0.5 °C/W, what is the maximum thermal resistance of the heat sink? Suppose the maximum temperature is 125 °C, and the ambient temperature is 25 °C; then the  is 100 °C. The heat sink's thermal resistance to ambient must then be 0.5 °C/W or less.

is 100 °C. The heat sink's thermal resistance to ambient must then be 0.5 °C/W or less.

Transmittance

A third term, thermal transmittance, incorporates the thermal conductance of a structure along with heat transfer due to convection and radiation. It is measured in the same units as thermal conductance and is sometimes known as the composite thermal conductance. The term U-value is another synonym.

Summary

In summary, for a plate of thermal conductivity k (the k value [4]), area A and thickness t:

- thermal conductance = k/t, measured in W·K−1·m−2;

- thermal resistance (R-value) = t/k, measured in K·m²·W−1;

- thermal transmittance (U-value) = 1/(Σ(t/k)) + convection + radiation, measured in W·K−1·m−2.

- K-value refers in Europe to the total insulation value of a building. K-value is obtained by multiplying the form factor of the building (= the total inward surface of the outward walls of the building divided by the total volume of the building) with the average U-value of the outward walls of the building. K value is therefore expressed as (m2·m-3)·(W·K-1·m-2) = W·K-1·m-3. A house with a volume of 400 m³ and a K-value of 0.45 (the new European norm. It is commonly referred to as K45) will therefore theoretically require 180 W to maintain its interior temperature 1 K above exterior temperature. So, to maintain the house at 20 °C when it is freezing outside (0 °C), 3600 W of continuous heating is required.

Examples

In metals, thermal conductivity approximately tracks electrical conductivity according to the Wiedemann-Franz law, as freely moving valence electrons transfer not only electric current but also heat energy. However, the general correlation between electrical and thermal conductance does not hold for other materials, due to the increased importance of phonon carriers for heat in non-metals. As shown in the table below, highly electrically conductive silver is less thermally conductive than diamond, which is an electrical insulator.

Thermal conductivity depends on many properties of a material, notably its structure and temperature. For instance, pure crystalline substances exhibit very different thermal conductivities along different crystal axes, due to differences in phonon coupling along a given crystal axis. Sapphire is a notable example of variable thermal conductivity based on orientation and temperature, with 35 W/(m·K) along the c-axis and 32 W/(m·K) along the a-axis.[5]

Air and other gases are generally good insulators, in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets which prevent large-scale convection. Examples of these include expanded and extruded polystyrene (popularly referred to as "styrofoam") and silica aerogel. Natural, biological insulators such as fur and feathers achieve similar effects by dramatically inhibiting convection of air or water near an animal's skin.

Light gases, such as hydrogen and helium typically have high thermal conductivity. Dense gases such as xenon and dichlorodifluoromethane have low thermal conductivity. An exception, sulfur hexafluoride, a dense gas, has a relatively high thermal conductivity due to its high heat capacity. Argon, a gas denser than air, is often used in insulated glazing (double paned windows) to improve their insulation characteristics.

Thermal conductivity is important in building insulation and related fields. However, materials used in such trades are rarely subjected to chemical purity standards. Several construction materials' k values are listed below. These should be considered approximate due to the uncertainties related to material definitions.

The following table is meant as a small sample of data to illustrate the thermal conductivity of various types of substances. For more complete listings of measured k-values, see the references.

Experimental values

This is a list of approximate values of thermal conductivity, k, for some common materials. Please consult the list of thermal conductivities for more accurate values, references and detailed information.

| Material | Thermal conductivity W/(m·K) |

| Silica Aerogel | 0.004 - 0.04 |

| Air | 0.025 |

| Wood | 0.04 - 0.4 |

| Hollow Fill Fibre Insulation Polartherm | 0.042 |

| Alcohols and oils | 0.1 - 0.21 |

| Polypropylene | 0.25 [6] |

| Mineral oil | 0.138 |

| Rubber | 0.16 |

| LPG | 0.23 - 0.26 |

| Cement, Portland | 0.29 |

| Epoxy (silica-filled) | 0.30 |

| Epoxy (unfilled) | 0.59 |

| Water (liquid) | 0.6 |

| Thermal grease | 0.7 - 3 |

| Thermal epoxy | 1 - 7 |

| Glass | 1.1 |

| Soil | 1.5 |

| Concrete, stone | 1.7 |

| Ice | 2 |

| Sandstone | 2.4 |

| Stainless steel | 12.11 ~ 45.0 |

| Lead | 35.3 |

| Aluminium | 237 (pure) 120—180 (alloys) |

| Gold | 318 |

| Copper | 401 |

| Silver | 429 |

| Diamond | 900 - 2320 |

| Graphene | (4840±440) - (5300±480) |

Physical origins

Heat flux is exceedingly difficult to control and isolate in a laboratory setting. Thus at the atomic level, there are no simple, correct expressions for thermal conductivity. Atomically, the thermal conductivity of a system is determined by how atoms composing the system interact. There are two different approaches for calculating the thermal conductivity of a system.

- The first approach employs the Green-Kubo relations. Although this employs analytic expressions which in principle can be solved, in order to calculate the thermal conductivity of a dense fluid or solid using this relation requires the use of molecular dynamics computer simulation.

- The second approach is based upon the relaxation time approach. Due to the anharmonicity within the crystal potential, the phonons in the system are known to scatter. There are three main mechanisms for scattering:

- Boundary scattering, a phonon hitting the boundary of a system;

- Mass defect scattering, a phonon hitting an impurity within the system and scattering;

- Phonon-phonon scattering, a phonon breaking into two lower energy phonons or a phonon colliding with another phonon and merging into one higher energy phonon.

Lattice waves

A kinetic theory of solids follows naturally from the standpoint of the normal modes of vibration in an elastic crystalline solid (see Einstein solid and Debye model) – from the longest wavelength (or fundamental frequency of the body) to the highest Debye frequency (that of a single particle). There are simple equations derived to describe the relationship of these normal modes to the mechanisms of thermal phonon wave propagation as represented by the superposition of elastic waves—both longitudinal (acoustic) and transverse (optical) waves of atomic displacement. [7] [8] [9] [10]

The velocities of longitudinal acoustic phonons in condensed matter are directly responsible for the thermal conductivity which levels out temperature differentials between compressed and expanded volume elements. For example, the thermal properties of glass are interpreted in terms of an approximately constant mean free path for lattice phonons. Furthermore, the value of the mean free path is of the order of magnitude of the scale of structural (dis)order at the atomic or molecular level. [11][12][13]

Thus, heat transport in both glassy and crystalline dielectric solids occurs through elastic vibrations of the lattice. This transport is limited by elastic scattering of acoustic phonons by lattice defects. These predictions were confirmed by the experiments of Chang and Jones on commercial glasses and glass ceramics, where mean free paths were limited by "internal boundary scattering" to length scales of 10−2 cm to 10−3 cm. [14][15]

The phonon mean free path has been associated directly with the effective relaxation length for processes without directional correlation. Thus, if Vg is the group velocity of a phonon wave packet, then the relaxation length  is defined as:

is defined as:

where t is the characteristic relaxation time. Now, since longitudinal waves have a much greater group or "phase velocity" than that of transverse waves, Vlong is much greater than Vtrans, the relaxation length or mean free path of longitudinal phonons will be much greater. Thus, thermal conductivity will be largely determined by the speed of longitudinal phonons. [14][16]

Regarding the dependence of wave velocity on wavelength or frequency (aka "dispersion"), low-frequency phonons of long wavelength will be limited in relaxation length by elastic Rayleigh scattering. This type of light scattering form small particles is proportional to the fourth power of the frequency. For higher frequencies, the power of the frequency will decrease until at highest frequencies scattering is almost frequency independent. Similar arguments were subsequently generalized to many glass forming substances using Brillouin scattering. [17][18] [19] [20]

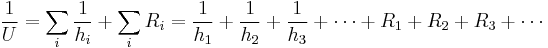

Controlling resistance

Often in heat transfer the concept of controlling resistance is used to determine how to either increase or decrease heat transfer. Heat transfer coefficients represent how much heat is able to transfer through a defined region of a heat transfer area. The inverse of these coefficients are the resistances of those areas. If a wall can be considered, it would have a heat transfer coefficient representing convection on each side of the wall, and one representing conduction through the wall. To obtain an overall heat transfer coefficient, the resistances need to be summed up.

Due to the nature of the above reciprocal relation, the smallest heat transfer coefficient (h) or the largest resistance is generally the controlling resistance as it dominates the other terms to the point that varying the other resistances will have little impact on the overall resistance:

-

or

or

Thus the controlling resistance can be used to both simplify heat transfer calculations and manipulate a system to a desired resistance value.

- Note: In the textile industry, a tog value may be quoted as a measure of thermal resistance in place of a measure in SI units.

Equations

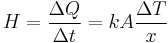

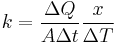

First, we define heat conduction, H:

where  is the rate of heat flow, k is the thermal conductivity, A is the total cross sectional area of conducting surface, ΔT is temperature difference, and x is the thickness of conducting surface separating the 2 temperatures. Dimension of thermal conductivity = M1L1T-3K-1

is the rate of heat flow, k is the thermal conductivity, A is the total cross sectional area of conducting surface, ΔT is temperature difference, and x is the thickness of conducting surface separating the 2 temperatures. Dimension of thermal conductivity = M1L1T-3K-1

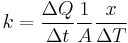

Rearranging the equation gives thermal conductivity:

(Note:  is the temperature gradient)

is the temperature gradient)

I.E. It is defined as the quantity of heat, ΔQ, transmitted during time Δt through a thickness x, in a direction normal to a surface of area A, per unit area of A, due to a temperature difference ΔT, under steady state conditions and when the heat transfer is dependent only on the temperature gradient.

Alternatively, it can be thought of as a flux of heat (energy per unit area per unit time) divided by a temperature gradient (temperature difference per unit length)

Typical units are SI: W/(m·K) and English units: Btu/(h·ft·°F). To convert between the two, use the relation 1 Btu/(h·ft·°F) = 1.730735 W/(m·K). [Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 7th Edition, Table 1-4]

See also

- Heat conduction

- Heat transfer

- Heat transfer mechanisms

- Insulated pipes

- Physics of glass

- R-value

- Specific Heat

- Thermal bridge

- Thermal contact conductance

- Thermal diffusivity

- Thermal grease

- Thermal resistance in electronics

- Thermal rectifier

- Thermistor

- Thermocouple

- Electrical conductivity

References

- ↑ IEEE Standard 442-1981- IEEE guide for soil thermal resistivity measurements, doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.1981.81018

- ↑ IEEE Standard 98-2002 - Standard for the Preparation of Test Procedures for the Thermal Evaluation of Solid Electrical Insulating Materials, doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2002.93617

- ↑ ASTM Standard D5334-08 - Standard Test Method for Determination of Thermal Conductivity of Soil and Soft Rock by Thermal Needle Probe Procedure, doi:10.1520/D5334-08

- ↑ Definition of k value from Plastics New Zealand

- ↑ http://www.almazoptics.com/sapphire.htm

- ↑ Walter Michaeli, Extrusion Dies for Plastics and Rubber, 2nd Ed., Hanser Publishers, New York, 1992.

- ↑ Einstein, A., Plancksche Theorie der Strahlung und die Theorie der Spezifischen Wärme, Ann. Der Physik, Vol. 22, p. 180 (1907); Berichtigung zu meiner Arbeit: Die Plancksche Theorie der Strahlung etc., Vol. 22, p. 800 (1907)

- ↑ P. Debye (1912). "Zur Theorie der spezifischen Wärme". Ann. Der Physik 39: 789.

- ↑ Born, M., von Karman, L., Phys. Zeitschr., Vol. 13, p. 297 (1912); vol. 14, p. 15 (1913)

- ↑ Blackman, M., Contributions to the Theory of the Specific Heat of Crystals. I. Lattice Theory and Continuum Theory, Proc. Roy. Soc. A, vol. 148, p. 365 (1935); II. On the Vibrational Spectrum of Cubical Lattices and Its Application to the Specific Heat of Crystals, vol. 148, p. 384 (1935); III. On the Existence of Pseudo-T3 Regions in the Specific Heat Curve of a Crystal, vol. 149, p. 117 (1935); Contributions to the Theory of Specific Heat. IV. On the Calculation of the Specific Heat of Crystals from Elastic Data, Vol. 149, p. 126 (1935); On the Vibrational Spectrum of a Three Dimensional Lattice, vol. 159, p. 416 (1937); Some Properties of the Vibrational Spectrum of a Lattice, Math. Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc., vol. 33, p. 94 (1937)

- ↑ H.M. Rosenburg (1963). Low Temperature Solid State Physics. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198519109.

- ↑ C.J. Kittel (1946). "Ultrasonic Propagation in Liquids. II. Theoretical Study of the Free Volume Model of the Liquid State". J. Chem. Phys. 14: 614. doi:10.1063/1.1724073.

- ↑ C.J. Kittel (1949). "Interpretation of the Thermal Conductivity of Glasses". Phys. Rev. 75: 972. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.75.972.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 P.G. Klemens (1951). "The Thermal Conductivity of Dielectric Solids at Low Temperatures". Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A 208: 108. doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0147.

- ↑ G.K. Chan, R.E Jones (1962). "Low-Temperature Thermal Conductivity of Amorphous Solids". Phys. Rev. 126: 2055. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.126.2055.

- ↑ I. Pomeranchuk (1941). "Thermal conductivity of the paramagnetic dielectrics at low temperatures". J. Phys.(USSR) 4: 357. ISSN 0368-3400.

- ↑ R.C. Zeller, R.O. Pohl (1971). "Thermal Conductivity and Specific Heat of Non-crystalline Solids". Phys. Rev. B 4: 2029. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.4.2029.

- ↑ W.F. Love (1973). "Low-Temperature Thermal Brillouin Scattering in Fused Silica and Borosilicate Glass". Phys. Rev. Lett. 31: 822. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.31.822.

- ↑ M.P. Zaitlin, M.C. Anderson (1975). "Phonon thermal transport in noncrystalline materials". Phys. Rev. B 12: 4475. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.12.4475.

- ↑ M.P. Zaitlin, L.M. Scherr, M.C. Anderson (1975). "Boundary scattering of phonons in noncrystalline materials". Phys. Rev. B 12: 4487. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.12.4487.

Further reading

- Callister, William (2003). "Appendix B". Materials Science and Engineering - An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons, INC. pp. 757. ISBN 0-471-22471-5.

- Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; & Walker, Jearl(1997). Fundamentals of Physics (5th ed.). John Wiley and Sons, INC., NY ISBN 0-471-10558-9.

- P A Hilton Ltd., "Thermal Conductivity of Liquids and Gases Unit." P A Hilton. <http://www.p-a-hilton.co.uk/H471.pdf>

- Srivastava G. P (1990), "The Physics of Phonons." Adam Hilger, IOP Publishing Ltd, Bristol.

- TM 5-852-6 AFR 88-19, Volume 6 (Army Corp of Engineers publication)

External links

- Table with the Thermal Conductivity of the Elements

- Calculation of the Thermal Conductivity of Glass Calculation of the Thermal Conductivity of Glass at Room Temperature from the Chemical Composition

- Viscosity and Thermal Conductivity Equations for Nitrogen, Oxygen, Argon, and Air

- Conversion of thermal conductivity values for many unit systems